The buzzword ‘sustainable’ (and ‘sustainability’) is seemingly overused these days, having lost much of its meaning as a result of a hijacking of the term through marketing campaigns. While I still use the term more often than not, I prefer to discuss holistic approaches to architecture, design, and the built environment.

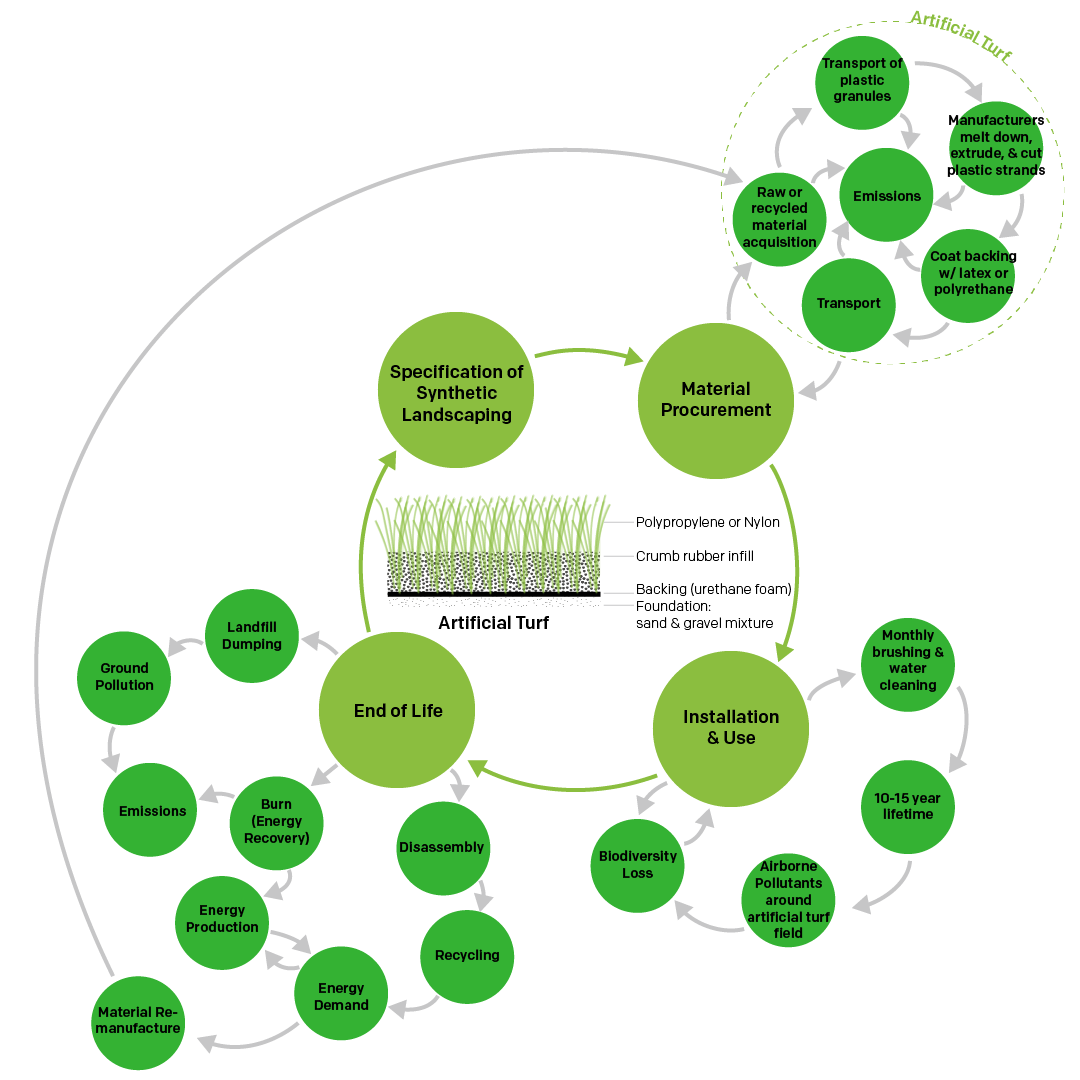

‘Holistic’, to me, means all-encompassing; it takes into account the three pillars of sustainability: environment, social, and economic, while also considering the up-and-down-stream effects of (design) choices. A holistic perspective of an issue or project can be gained through the use of systems thinking. An example of a systems thinking diagram can be seen below.**

Many of our indoor spaces are filled with endocrine-disrupting building materials and finishes

Understanding consequences

Systems thinking is a useful tool for understanding complex issues. It is an instrument of rationality that can expose (or explain) how things are connected and the nature of their connections. Employing a systems thinking approach can create understanding of actions and consequences, especially in understanding the reach of one’s own impact.

We have assembled a list of questions we ask manufacturers to capture a full understanding of the materials in question

Touching on all three pillars, a particular area of concern over which architects and designers have a great deal of power is material specification. Extraction and manufacturing of raw materials for construction not only impacts the immediate environment from which it is removed, but quite often consumes high volumes of energy in its extraction, manufacturing, and transport to the construction site. The qualifications of a product can be measured against environmental indicators, such as embodied energy, global warming potential, water consumption, ozone depletion, acidification, and carbon sequestration, amongst others, but not many manufacturers readily provide this information.

Human considerations

Not only must designers consider the embodied energy of materials but also the social and economic impacts of resource extraction, often unseen given our global economy. We must also consider the labourers extracting, manufacturing, and installing our products: whether they are paid a fair, living wage and are given healthy work conditions.

Over the last year of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has also been a rise in interest of health and wellbeing in interior spaces: in the office, at home, and in public spaces. Many of our indoor spaces are filled with endocrine-disrupting building materials and finishes, many of which are currently unregulated but are known to impact fertility and overall health.

‘Specifiers have a duty’

As architects and material specifiers, we have a duty to all of the stakeholders across the value chain to understand the material we specify in the buildings we design. At Chetwoods Thrive, we have assembled a list of questions we ask manufacturers to capture a full understanding of the materials in question. However, we must be met half-way by these same manufacturers; not all architectural outfits have the time and capacity to chase down each and every material qualification.

Manufacturers can use this list as a guide in providing greater transparency of their products. In parallel, the Chetwoods Thrive team has consulted with the NBS to expand their material filter options in line with our questions.

An ever-expanding number of considerations must be met by practicing architects and specifiers. To meet these demands, we must have a full understanding of the impact of our designs and material selections, which can be achieved through a holistic approach.

**Systems thinking further learning – Youtube video (10.33–25.24)

Content Team

Work in Mind is a content platform designed to give a voice to thinkers, businesses, journalists and regulatory bodies in the field of healthy buildings.